Beyond the Applause: The Silent Tragedy of Uganda’s "Uneducated" Legends and the Fight to Reclaim Dignity

For decades, talented footballers traded their books for boots, only to find themselves locked out of the boardroom and the technical bench when their legs gave out. FFI explores the systemic trap of illiteracy and poverty—and how we are fixing it.

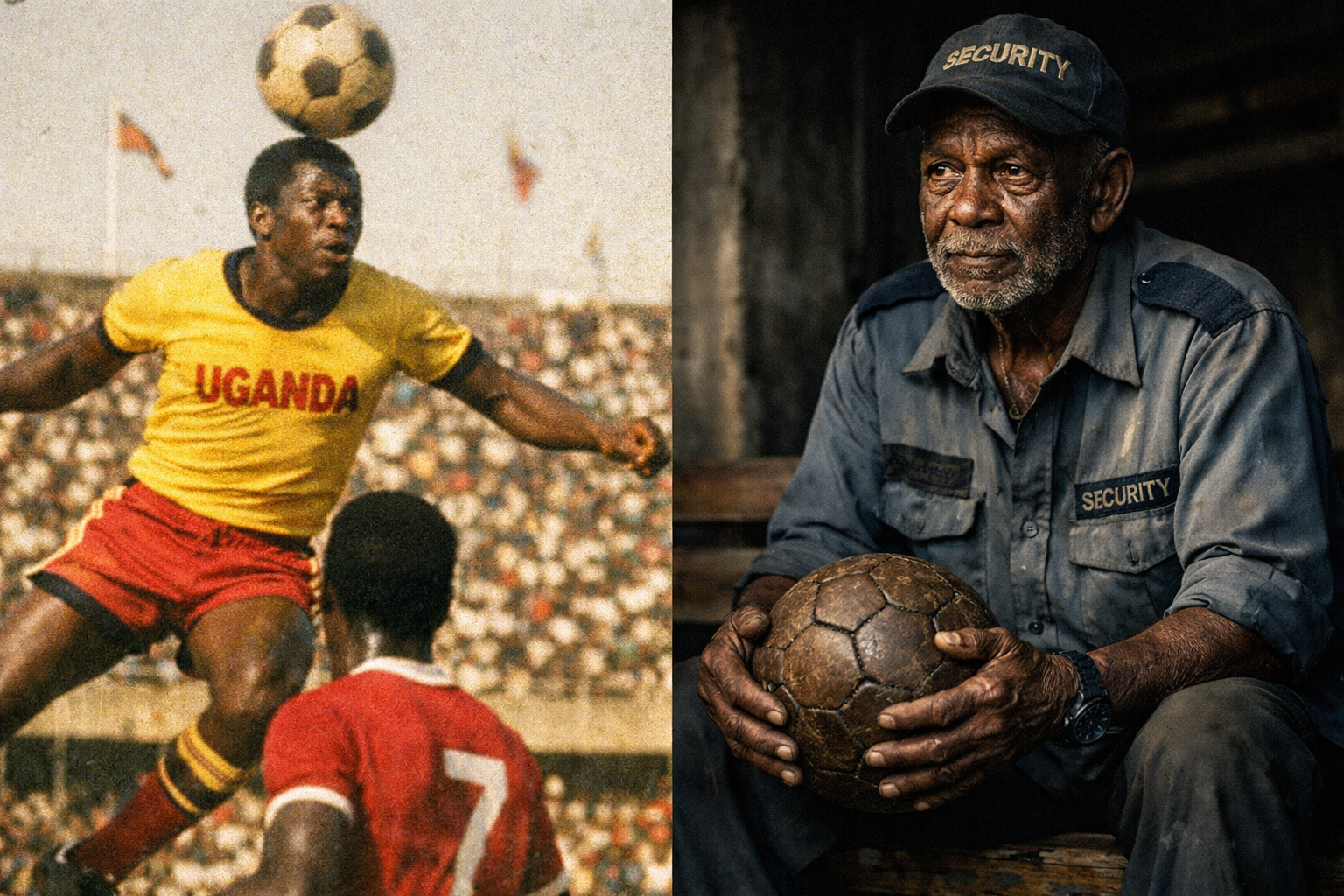

KAMPALA – In the 1970s and 80s, the streets of Kampala would freeze for the stars of Simba, Express, KCC, and Coffee FC. They were icons. They dined with Presidents. They were paid in applause, adoration, and the thrill of the victory lap at a packed Nakivubo War Memorial Stadium.

But when the lights of Nakivubo dimmed and the roar of the crowd faded into history, a cold reality set in.

Today, the Former Footballers Initiative (FFI) is confronting a crisis that has been whispering in the corridors of Ugandan football for forty years. It is a crisis not just of poverty, but of structural exclusion. We are witnessing a generation of heroes who, having sacrificed their education for the nation’s glory, found themselves "used up" by age 35, possessing neither the money to survive nor the literacy required to lead the sport they helped build.

The Great Trade-Off: Boots Over Books

To understand the current plight, we must look at the amateur structure of the 20th century. Football in Uganda was institutional. Players were "employed" by Uganda Commercial Bank (UCB), Coffee Marketing Board, KCC, Maroon (Prisons), or Simba (Army).

However, historical analysis shows these employment contracts were often a mirage. Talented teenagers were plucked from schools like Old Kampala or Kibuli with promises of "soft lives." They were given clerical titles on payrolls to justify their match allowances, but they spent their days on the training pitch, not at the desk.

"We were told that football was the job," recalls a veteran midfielder who wished to remain anonymous. "Why sit in a classroom when you can travel to Cairo and Addis Ababa? We stopped reading. We stopped learning."

This trade-off was fatal. When their knees buckled or speed faded in their early 30s, the institutions retrenched them. They had no savings (as the sport was amateur), but worse, they had no transferable skills.

The "Double Death" of a Career: The Administrative Lockout

The most painful aspect of this legacy—and one rarely discussed—is why so many legends vanish from the sport entirely.

Logic dictates that a retired legend should become a Coach, a CEO, a General Secretary, or a Club Manager. But modern football has professionalized. The Federation of Uganda Football Associations (FUFA) and CAF now require certification for these roles.

To sit on a technical bench, one needs a CAF C or B License. These courses require reading tactical manuals, writing reports, and passing written exams.

To manage a club requires understanding spreadsheets, contracts, and email correspondence.

This is the tragedy: A player may know the geometry of a pass better than anyone in the country, but if he lacks basic literacy because he abandoned school in Senior 2 to play for a Club, he is locked out. He cannot coach. He cannot manage.

The game uses them, and when they are done, the game’s new bureaucratic walls lock them out. They are exiled from the only world they know.

The Downward Spiral: Survival, Addiction, and Illness

Excluded from administration and lacking professional qualifications for the corporate world, many legends free-fall into the informal economy.

The FFI has documented heartbreaking cases of former national stars reducing themselves to casual laborers, market porters, and security guards at private residences—jobs that offer no dignity to men who once wore the national colors.

This loss of status is a breeding ground for Clinical Depression. Dr. Ronald Kisolo and other sports physicians have long noted the correlation between retirement and mental health crises.

The Solace of the Bottle: Depression often leads to alcoholism as a coping mechanism.

The Health Crisis: The lifestyle of the 90s, combined with a lack of awareness, left many vulnerable to the HIV/AIDS scourge. Today, without medical insurance or steady income to afford antiretrovirals or manage lifestyle diseases like diabetes and hypertension, our heroes are dying preventable deaths.

FFI: The Structural Correction

The Former Footballers Initiative was established not as a charity, but as a correctional mechanism for this historical error. We exist to break this cycle.

1. Reclaiming Livelihoods (The Business Pillar)

Under the leadership of Ssempijja Isaac, FFI is building systems that do not require degrees to operate, but do require discipline. These are designed to provide passive income that does not depend on a member's ability to read a corporate balance sheet or run 90 minutes.

2. The Education Intervention

Under Kimera Ronald (Head of Education), we are addressing the literacy gap.

For the Legends: We are partnering with vocational institutions (Jua Kali) to teach trade skills—mechanics, carpentry, agriculture—that allow a member to earn a living with their hands, restoring their independence.

For the Next Generation: This is our most vital message. FFI members are visiting schools and clubs to tell young players: "Look at me. I was a star, but I cannot sign a contract. Do not make my mistake. Play football, but get your degree."

3. Dignity in Healthcare

We cannot reverse the years lost, but we can cushion the landing. Our partnerships with medical service providers are looking to ensure that an illiterate, impoverished legend is treated with the same respect as a CEO when they walk into a hospital.

A Message to the Nation

When you see a former star walking in the shadows, do not judge them. Understand the system that produced them.

Ugandan football extracted their talent and left them empty. The FFI is here to refill that cup—with dignity, with sustainable business, and with a brotherhood that says: "You are valuable, with or without the jersey."